The student feels in control by seeing a direct link between his or her actions and an outcome and retains autonomy by having some choice about whether or how to undertake the task.

A new Center on Education Policy report, Student Motivation—An Overlooked Piece of School Reform, pulls together findings about student motivation from decades of major research conducted by scholars, organizations, and practitioners. The six accompanying background papers examine a range of themes and approaches, from the motivational power of video games and social media to the promise and pitfalls of paying students for good grades.

Researchers generally agree on four major dimensions that contribute to student motivation (below). At least one of these dimensions must be satisfied for a student to be motivated. The more dimensions that are met, and the more strongly they are met, the greater the motivation will be.

Four Dimensions of Motivation

- Competence — The student believes he or she has the ability to complete the task.

- Control / Autonomy — The student feels in control by seeing a direct link between his or her actions and an outcome and retains autonomy by having some choice about whether or how to undertake the task.

- Interest / Value — The student has some interest in the task or sees the value of completing

- Relatedness — Completing the task brings the student social rewards, such as a sense of belonging to a classroom or other desired social group or approval from a person of social importance to the student.

As the report authors note: The interplay of these dimensions—along with other dynamics such as school climate and home environment—is quite complex and varies not only among different students but also within the same student in different situations. Still, this basic framework can be helpful in designing or analyzing the impact of various strategies to increase students’ motivation.

The report singles out a number of approaches that can motivate unenthusiastic students including inquiry-based learning, service learning, extracurricular programs (like chess leagues) and creative use of technology.

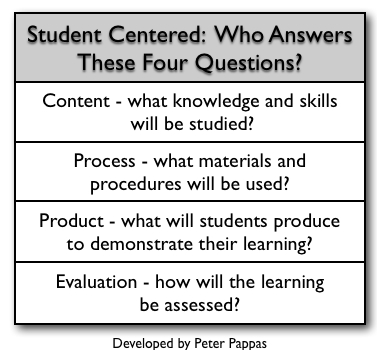

I think increase motivations begins with giving students more responsibility for critical decisions about what and how they learn. I detailed these in my post The Four Negotiables of Student Centered Learning and they are summarized in this table. Teachers need to consider the extent to which they are asking students to manage the four central elements of any lesson – content, process, product and assessment. Any or all can be decided by the teacher, by the students, or some of both. All will assist in building Common Core skills in deeper thinking and analysis.

Students also need guided practice in reflection. Reflection can be a challenging endeavor. It’s not something that’s fostered in school – typically someone else tells you how you’re doing! At best, students can narrate what they did, but have trouble thinking abstractly about their learning – patterns, connections and progress. One place to start is with the reflective prompts I developed in my Taxonomy of Reflection.

The CEP’s summary report and accompanying papers highlight actions that teachers, school leaders, parents, and communities can take to foster student motivation. The following are just a few of the many ideas included in the report:

- Programs that reward academic accomplishments are most effective when they reward students for mastering certain skills or increasing their understanding rather than rewarding them for reaching a performance target or outperforming others.

- Tests are more motivating when students have an opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge through low-stakes tests, performance tasks, or frequent assessments that gradually increase in difficulty before they take a high-stakes test.

- Professional development can help teachers encourage student motivation by sharing ideas for increasing student autonomy, emphasizing mastery over performance, and creating classroom environments where students can take risks without fear of failure

- Parents can foster their children’s motivation by emphasizing effort over ability and praising children when they’ve mastered new skills or knowledge instead of praising their innate intelligence.

Many aspects of motivation are not fully understood, the report and background papers caution, and most programs or studies that have shown some positive results have been small or geographically concentrated. “Because much about motivation is not known, this series of papers should be viewed as a springboard for discussion by policymakers, educators, and parents rather than a conclusive research review,” said Nancy Kober, CEP consultant and coauthor of the summary report. “This series can also give an important context to media stories about student achievement, school improvement, or other key education reform issues.”