It’s August and that’s back to school time. All across America teachers are sitting is staff development workshops. Some sessions are valuable, others will leave teachers wishing they could be setting up their classrooms.

Recently I had the chance to work with Marta Turner / NWRESD to design and administer a staff development grant from the Library of Congress and the TPS Western Region. The goal of the project was to give participating teachers skills in designing historical thinking skills lessons utilizing primary source documents from the Library of Congress’ vast online collection.

I saw it as a chance to demonstrate my first law of staff development

~ PD should model what you want to see in the classroom.

So in addition to mastering historical thinking skills utilizing LOC.gov, this workshop became a demonstration of the following:

How to flip your class:

Orientation to the LOC site was something better done on participants’ own time than in whole group. We utilized Versal (a free and stylish LMS) to offload that task to a flipped pre-course. Teachers arrived at the workshop with a working knowledge of LOC online resources , strategies for teaching historical thinking skills and ideas (and LOC documents) for their demonstration lesson.

Thanks for shepherding us through the process – a motivating demonstration of what’s possible with kids ~ Paul Monheimer, participant

Leveraging tech tools for design and collaboration:

Teachers collaborated in the pre-course using Google docs to design and curate examples of historical sourcing. I created YouTube tutorials to use throughout the pre-course and workshop session to blend the learning.

Teachers collected historical documents from the LOC into shared Google slides. This facilitated easy peer review and also served as an archive for materials in preparation for transfer to iBooks Author.

We used Google Hangouts to explore “how historians think” with Dr. Adam Franklin-Lyons – associate professor of history at Marlboro College.

Motivate with project-based learning:

Teachers were pleased that the workshop would produce lessons they could use. But right from the start they knew that they were not simply getting together to learn some strategies and create some lessons. They had an iBook to create and we only had two days onsite to do so. As educators, we talk about value of the authentic audience for our students but it applies to our teacher PD as well. (I held myself accountable to the same standard, since the major elements of the workshop were shared on my blog and via the Versal pre-course.)

Our participant teachers left the 2-day workshop energized knowing that their work was documented for our grant funders to replicate in other projects and proud that their lessons would be available as an iBook on iTunes in 51 countries around the world. Note: Time did not allow me to teach iBooks Author to the teachers, so I designed and edited the iBook later. For more on how I teach iBooks Author, see this iBA workflow post.

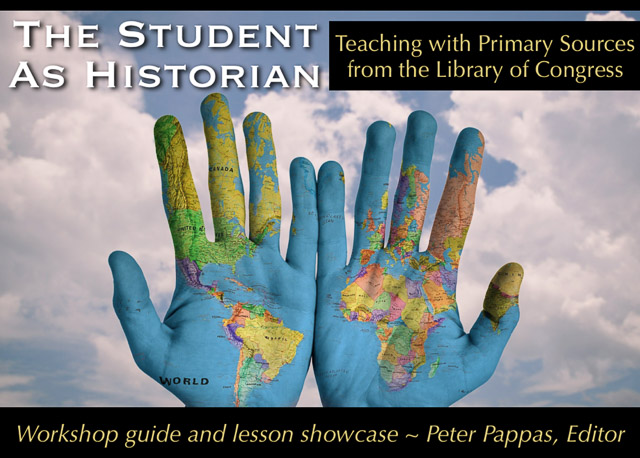

We are proud to share our iBook The Student As Historian ~ Teaching with Primary Sources from the Library of Congress. This ebook contains both the training materials and fourteen teacher-designed document-based questions for grades 4 through high school.

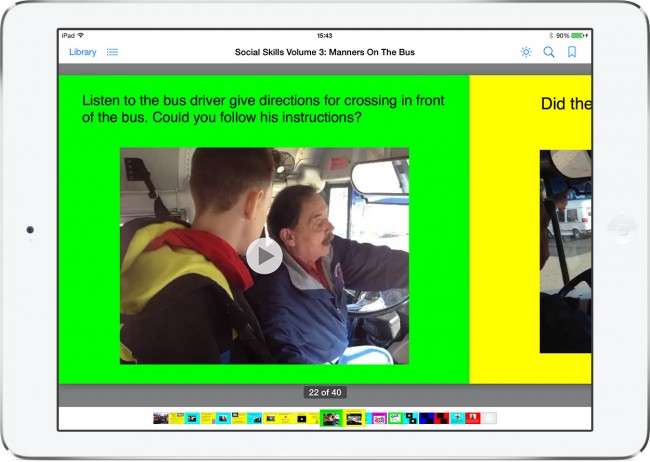

The lessons draw from a fascinating collection of text and multimedia content – documents, posters, photographs, audio, video, letter and other ephemera. “Stop-and-think” prompts based on CCSS skills guide students through analysis of the primary sources. Essential questions foster critical thinking. All documents include links back to the original source material so readers can remix the content into their own curated collections.

Download free at iTunes here. It’s viewable on Mac, iPad and iPhone 5 or newer. If those options don’t work for you, you can download it as a PDF The Student as Historian-PDF version 14 MB. (Interactive widgets will not function in pdf version)

Note: This is not an official publication of the Library of Congress and does not represent official Library of Congress communications.

Image credit: stokpic / Pixabay

Creative Commons CC0 Source

I recently was a contributor to a Education Week Teacher’s “Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo” column

I recently was a contributor to a Education Week Teacher’s “Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo” column