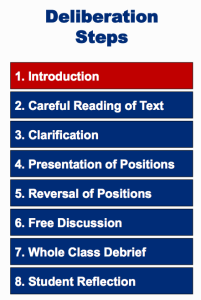

I’m planning for an upcoming full-day workshop for Chicago-area middle school teachers entitled “Think Like a Historian: Literacy and the Common Core.” The Common Core encourages students to more closely read a text (in all it’s multimedia formats) by answering three critical questions

- What did it say?

- How did it say it?

- What’s it mean to me?

If you were apply those questions to my workshop you might answer them like this:

- What did the workshop say? For all it’s controversies, the Common Core provides a basic road map for helping your students to “think like a historian” and enhance their literacy and critical thinking skills.

- How did the workshop say it? Don’t lecture at people. Model the strategies and let teachers experience them in a classroom-like setting.

- What’s it mean to me? What are the workshop’s strategies and perspectives that I could feasibly incorporate into my classroom to support Common Core skills?

Now that I’ve “flipped” the workshop, here’s a brief lesson in using Common Core questioning. I’m currently visiting Turkey and I thought I’d model a Common Core close reading of my visit to an Istanbul museum exhibit. I’ll dig a little deeper into the three questions with a few more prompts and provide brief answers as if I were a high school student reflecting on their experience.

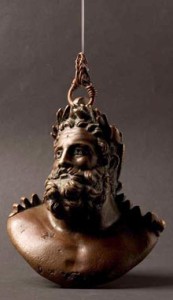

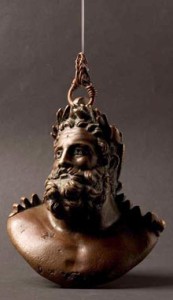

First the setting: I visited the “Anatolian Weights and Measures” exhibit at the Pera Museum in Istanbul. It’s one large room with exhibit cases around it’s perimeter. A very manageable number of artifacts, labeled in both Turkish and English. I spent about an hour there. So here goes – Common Core close reading prompts, followed by “student responses.” Left: Roman steelyard weight – Hercules

1. What did the text (artifacts / exhibit) say? Summarize the key ideas and provide supporting details.

A: The museum exhibit is a roomful of measurement tools – weight, volume, distance. When I first walked in I turned right and looked at some tools from the 1900s. As I continued around the wall I realized that I was going back in time. Sort of an interesting way to look at the artifacts.

As I progressed “back in time” to the Egyptians era, I realized how important measurement was to civilization. I realized that if you were going to trade things, you needed to measure them. The same was true for owning land. You needed to have a way to measure it. Plus people need to have some way to agree on the “official” measurements. That means the ancients needed some sort of government or rules for trade. You can see that many of the weights had “official” seals on them.The exhibit showed that the ancient Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks created standardized systems for measurement.

Common Core close reading prompts, followed by “student responses.”

2. How did the text (artifacts / exhibit) say it? How is it organized? Who created it and what were their goals? What patterns do you see?

A: I’ll answer this one from two perspectives – first the creators of the original artifacts and then the curators who designed the exhibit.

The weights were all designed to serve a function, but they were often very artistic as well. At first I wondered if that was because craftsmen wanted to personalize their work. Then I thought the artisans might have decorated the weights to make them harder to counterfeit. Ancients would want to be sure that weights were accurate and that some trader wasn’t ripping them off with a phony measurement. I think the weights were also designed to look official to give people confidence in the measurements they were getting.

The curators of the exhibit used a chronological approach to present the artifacts. But they also grouped items together by themes to help you make connections across time. For example there was a section featured mobile scales from different eras. They were designed for traders that needed scales that they could easily bring with them. That got me thinking of the long history of trade routes tranporting goods from far off lands.

18th C Money Changer’s Balance

18th C Money Changer’s Balance

3. How does it (artifacts / exhibit) mean to me? How does it connect to my life and views?

A – The exhibit is called “Anatolian Weights and Measures” and it makes it very clear that every artifact was found in that region. I think one of the goals of the curators was to prove that Turkey has had a long history of civilization and trade. The exhibit showcases thousands of years of measurement tools that reinforce the idea of Turkey as as the crossroad of different cultures. That echoes the image of modern Turkey as a gateway between Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. The exhibit also makes me realize that the idea of a global economy is actually not a new thing. People have been trading across vast distances for thousands of years.

In one way, in the exhibit reminded me of how some things never change. It seemed like there was little difference in the scales used in Egypt or the portable balance of 18th century money changer. The basic physics stayed the same. The Roman steelyard balance works using the same principals as a locker room scale with sliding weights.

But in another way, the exhibit reminded me how much the new technologies have changed things. The exhibit included a set of linked folding metal measuring rods that today are easily replaced by a small laser distance finder. They would could both measure distance, but the technology, accuracy and portability of the tools are dramatically different.

Image credit/ Pera Museum Pinterest

Like this:

Like Loading...

The NY Times Learning Network has just launched a new series of lesson plans called “Text to Text.” It’s a simple approach that pairs two written texts that “speak to each other.” I think it’s a Common Core close reading strategy that could be easily replicated by teachers across the curriculum – great way to blend nonfiction with fiction and incorporate a variety of media with written text.

The NY Times Learning Network has just launched a new series of lesson plans called “Text to Text.” It’s a simple approach that pairs two written texts that “speak to each other.” I think it’s a Common Core close reading strategy that could be easily replicated by teachers across the curriculum – great way to blend nonfiction with fiction and incorporate a variety of media with written text.